BEND, Ore. — Suicides rates are rising, and the role of guns is stark, unavoidable and contentious. So it may be remarkable that some health professionals have taken the unusual step of partnering with gun owners in firearm-friendly strategies for saving lives.

In Central Oregon, researchers worked with a family doctor and rural firearm owners to develop a suicide prevention message that respects the cultural values and rights of gun owners.

The resulting brochure they developed and tested evokes national patriotism, with a bald eagle against a U.S. Constitution and flag.

“We believe firearms are an American way of life — a constitutional right and a necessity in order to protect ourselves and our families,” says the text. “And with this RIGHT to bear arms comes RESPONSIBILITY.”

The Oregon pamphlet lists warning signs of suicide and offers advice for friends and family to take action to protect their loved ones who are going through a “rough patch.” The language, attitudes and action steps mimic the informal customs among gun owners, the researchers learned.

“One of the things we discovered was that firearm owners were having conversations about suicide prevention,” said Elizabeth Marino, an anthropologist at Oregon State University-Cascades in Bend, who designed the studies. “All this time, this work was going on outside of the knowledge and collaboration with public health.”

“They have people they’re worried about,” added Susan Keys, who retired from OSU-Cascades and is a public health program development consultant who helped lead the project.

“All we’re after is keeping people safe,” said Laura Pennavaria, a family doctor and chief medical officer of St. Charles Health System in Bend who helped develop the materials.

The Bend team is rolling out an online training course for Oregon doctors and other health care professionals that teaches health care professionals how to identify suicidal behavior. Similar efforts have emerged in states with high and rising suicide rates across the country, primarily as local responses to suicides. The Oregon program arose independently to help local doctors talk to patients at risk of suicide in rural communities.

Public health professionals in locations across the country have partnered with gun owners to develop safety training and suicide prevention messages targeted to gun shops, shooting ranges and citizens with concealed carry permits.

The partnerships are uneasy alliances between people who disagree about solutions to gun violence, such as legislation. However, those same people have a common goal: reduce suicides by reducing access to guns. In the United States, two out of every three deaths by firearm are suicide.

Involving firearms owners in developing suicide prevention messages and training may be flying largely under the radar, but proponents of the strategy dream of a day when the idea of friends keeping friends at risk of suicide away from guns has the same cultural resonance as friends not letting friends drive drunk.

For now, the Bend team knows its gun safety message sits well with rural Oregon gun owners.

Pennavaria became involved when patients began talking to her about their suicidal thoughts after a student shot himself at Bend High School. She was struck by a study that reported 64% of people who die by suicide had contact with their primary care provider within a year of death and 45% had contact within one month. The study included Oregonians.

Most people who kill themselves with firearms have no major suicide risk factors in their medical records, such as mental health issues, substance abuse, or previous suicide attempts, found postdoctoral researcher Jennifer Boggs and her colleagues at the Institute for Health Research at Kaiser Permanente Colorado in Aurora.

Even for people at risk of suicide or who had attempted suicide in the past month, only one-third had notes in their medical records of firearm discussions with patients, Boggs and her colleagues found in a follow-up study.

Standard public health approaches to gun safety may backfire and alienate the people they intend to help.

“I’ve been asked before at a doctor’s visit if I own guns,” said Bill Littlefield, an entrepreneur and a board member of the Bend chapter of the Oregon Hunters Association. His internal response is, “it’s none of your damn business.”

The question makes him suspicious that it may be a thinly veiled attack on guns.

“Is this really about helping people with depression and mental illness or are there ulterior motives, such as finding another way to take guns from people?” Littlefield said.

Still, he shares the goal of preventing suicides. “The question is, how do you support the goodness of this cause in a practical sense but don’t allow it to go wild?”

The Bend researchers believe their culturally sensitive conversations can help prevent suicides outside of the doctor’s office too — in gun shops, for example — but they admit it’s not easy. Guns and gun deaths are a polarizing topic, and trust is crucial. Both the researchers and gun owners were wary of a reporter’s calls and the potential of the news media to sow dissension and mistrust.

“I would like to see an article that says firearm owners are an ally in suicide prevention,” Keys said. “Firearm owners as a group sometimes get the short end of the stick. People who own guns need to have an equal say at the table.”

In New Hampshire, the suicide prevention collaboration between public health professionals and gun owners has been going on longer. The NH Firearms Safety Coalition began in the early 1990s when Elaine Frank became the director of the injury prevention program at Dartmouth College, about the same time data showed a rise in youth suicides by gun.

“Both pro-gun and anti-gun folks were saying the same thing about safe storage,” Frank said. “Everyone agreed.” So she created a coalition around firearm safety to prevent gun deaths among young people.

If Frank wanted to do something about guns, she needed to talk to Ralph Demicco, others advised. He was the owner of Riley’s Sportshop, then the highest gun volume store in the state, and a well-known advocate for guns and the second amendment.

When Frank asked him to join the coalition, “it gave me pause,” said Demicco, now retired. His retail mentor, Richard “Dick” Riley, who went on to serve as president of the National Rifle Association, had preached the importance of being a responsible member of the community. In fact, guns were not sold on commission, and he told his clerks they had no obligation to sell anything, especially if a person appeared to be under the influence, incoherent or didn’t display firearms knowledge.

Demicco joined the coalition for two reasons.

“I wanted to watchdog the group and make sure it was about gun safety and not anti-gun, and I wanted to spread the word.”

With money from a local gun manufacturer (Sturm, Ruger & Co.), the coalition developed and distributed youth gun safety posters in gun shops. The coalition fell dormant.

“Then about 10 years ago, Elaine called me again,” Demicco said. She said a few niceties and then asked him if he was aware that in the space of six days, three different people bought guns at his store and took their lives. “I was aghast,” he said.

The coalition started meeting regularly again and added other gun enthusiasts and public health professionals, including Catherine Barber, director of the Means Matter program at Harvard School of Public Health, a program that focuses on reducing a suicidal person’s access to highly lethal means.

They created the Gun Shop Project, first consulting with owners of gun shops and shooting ranges, and then hanging posters and suicide hotline cards. “We’re anti-suicide, not anti-gun,” said Demicco, who likes the comparison to the friends-don’t-let-friends-drive-drunk campaign that reduced deaths by effectively discouraging drunk people from getting behind the wheel.

“I’ve probably gotten more push-back from the left than from the right,” Frank said. She recounts a brief presentation she made about the Gun Shop Project to fellow board members of the NH Public Health Association. “One woman raised her hand and said, ‘Elaine, this is very nice, but what are you doing about gun control?’” Frank replied, “This is not about gun control. This is a different approach.”

The NH Firearm Safety Coalition has shared its information and approach with gun shop enthusiasts and public health people in other states, including Maryland, New York, Missouri, Texas and Utah.

“I’ve never worked with a nicer group of people who happen to be politically on the other side of the fence than anything I’ve ever done,” said Demicco about the secret to their success. “We don’t preach pro-guns per se, and they don’t preach anti-guns per se. We focus on anti-suicide.”

Three years ago, American Foundation for Suicide Prevention partnered on a program with the National Shooting Sports Foundation, an industry group for gun retailers and manufacturers based in Newtown, Connecticut. The program was modeled after the New Hampshire Gun Shop Project and championed by the NSSF president, a former coalition member and former CEO of Sturm, Ruger & Co.

Before the Gun Shop Project took off, a gun-owning clinical psychologist in New Hampshire had created a video to help train his health care staff about how to talk about gun storage with parents of teens at risk of suicide. Frank and Barber built that idea into a training program for how to talk comfortably and effectively with gun owners at risk of suicide. The training is called Counseling on Access to Lethal Means (CALM). A new version was posted in December to the website of the information clearinghouse, Suicide Prevention Resource Center. Two years ago, Frank held CALM trainings in the Portland Metropolitan area and Southern Oregon.

The strategy is resonating across the country. A recent public service announcement from Utah sums it up the culturally sensitive suicide prevention message, Barber said.

“In under 30 seconds, here is something that encapsulates the whole message of resilience and recovery, not waiting for a person to ask for help, that friends are aware when friends are having trouble but don’t want to get into the weeds emotionally, a real bro way for showing concern and assisting a friend, and not waiting until a person says they’re suicidal,” she said.

In Oregon, the gun-friendly public health message developed by Keys, Pennavaria, Marino with firearms owners passed the strictest test imaginable to Kimberly Repp, an epidemiologist with the Washington County suicide prevention program who was raised on the Oregon Coast.

“I’m the only person in my family who is not a lifetime member of the NRA,” she said. “When I saw this brochure, I actually took it home. It passed the test of not setting off alarm bells in my dad. It’s truly exceptional work in terms of culturally competent in gun ownership and cultural competent in suicide prevention. I know hundreds of people who own guns, and I don’t know anyone who wants people to die by suicide.”

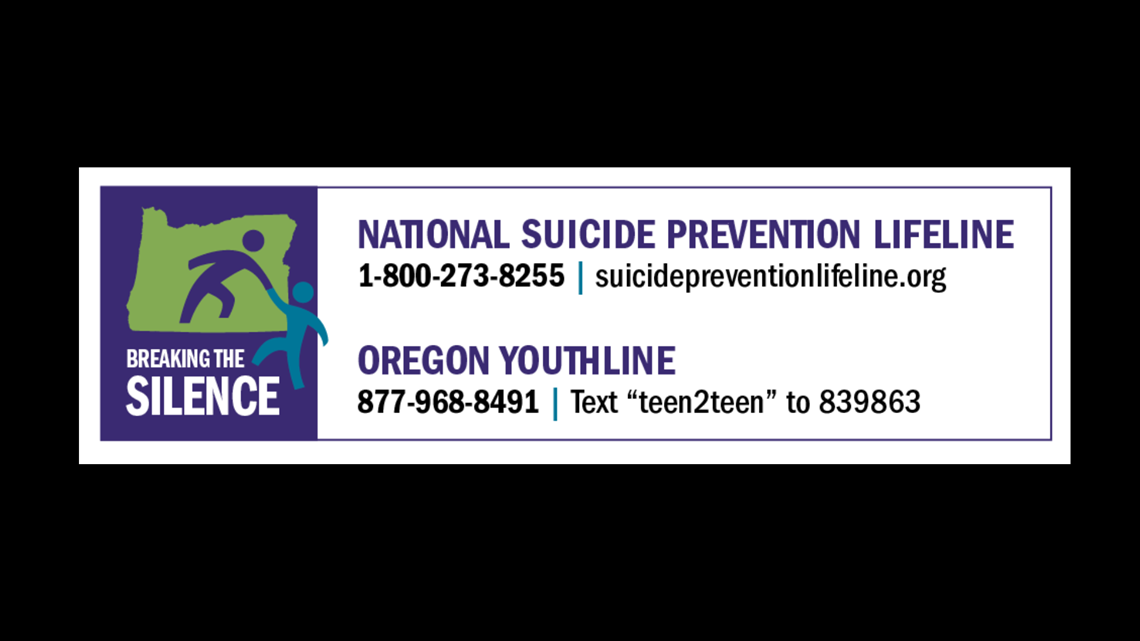

Breaking the Silence

This month, newsrooms across the state are highlighting the public health crisis of death by suicide. Our goal of “Breaking the Silence” is to not only put a spotlight on a problem that claimed the lives of more than 800 Oregonians last year, but also examine research into how prevention can and does work and offer our readers, listeners and viewers resources to help if they – or those they know – are in crisis.

More than 40 newsrooms contributed stories when the project first launched in April. This September media outlets are producing new stories in recognition of National Suicide Prevention Month. When possible, we will promote each other’s stories, and all of them can be found on breakingthesilenceor.com

Online resources:

- Counseling Access to Lethal Means (CALM) training: www.sprc.org/resources-programs/calm-counseling-access-lethal-means

- American Foundation for Suicide Prevention and National Shooting Sports Foundation’s Suicide Prevention Toolkit: www.nssf.org/safety/suicide-prevention-toolkit

- Harvard University’s Means Matter program: www.hsph.harvard.edu/means-matter

- Central Oregon Suicide Prevention brochure (at right): http://oregonfirearmsafety.org

- Utah Suicide Prevention Coalition PSA-Gun Range: https://vimeo.com/175761640

The story was published 16 August 2019 in Pulse, the Bend Bulletin’s quarterly health magazine. Link to original story

Carol Cruzan Morton is an independent health and science journalist based in Oregon.