PORTLAND, Ore. — The smallest lamprey in Oregon is back in its namesake lake after being pushed to the brink of extinction.

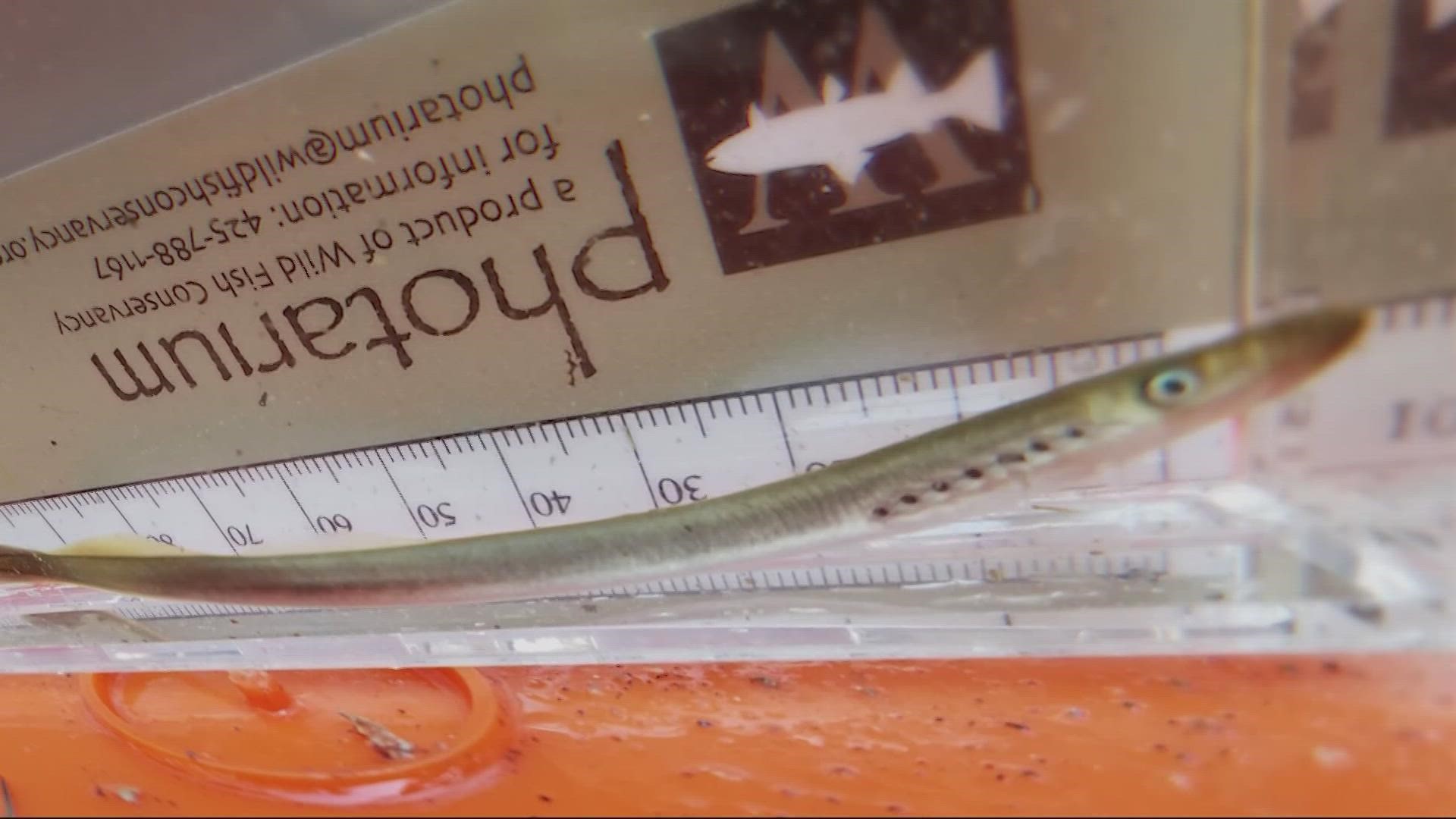

The Miller Lake lamprey, which lives only in Miller Lake and its surrounding watershed in the southern Oregon Cascades, is only three to six inches long and feeds parasitically off other fish.

Ben Clemens, the lamprey coordinator for the Oregon Department of Fish and Wildlife, said the fish was nearly eradicated 70 years ago when wildlife officials grew concerned that the lamprey were harming game fish, brown and rainbow trout, that they had stocked in the lake.

Officials, without even knowing the Miller Lake lamprey was a distinct species, began trying to eradicate the fish to keep it from harming the trout.

“They didn’t know the species at the time, but they were concerned about this because these were sport fisheries they were trying to support,” Clemens said. “They started putting logs and screens in creeks that went into the lake to prevent the lamprey from spawning.”

Clemens said officials also erected a barrier downstream from Miller Lake, and even went a step further.

“They put toxaphene, a highly toxic pesticide, into the lake and its tributaries to eradicate the species,” Clemens said.

The Miller Lake lamprey wasn’t actually identified as its own species until the 1970s, when researchers at Oregon State University were studying some preserved specimens.

“At that time, they were thought to be extinct,” Clemens said.

Fast forward a few decades to the early 1990s and the diminutive lamprey were found living well downstream of their original home. The state removed the barrier downstream in 2005 and a conservation plan, one of the state’s earliest for a fish species, was adopted.

Starting in 2010, a team of state officials began translocating young lamprey — capturing them downstream from the lake and moving them to tributaries above in the hopes they would repopulate it.

Over this last summer, they found out their hopes had been realized when some members of the team were fishing at the lake.

“They pulled up several trout that had fresh lamprey wounds on them,” Clemens said. “They knew where to look because they were helping and that’s indication the lamprey are back in the lake.”

The Miller Lake lamprey are not convenient posterchildren for conservation. They’re small and parasitic. They live in a remote part of the state and, unless you were looking for them, you might know they exist.

But the species has roots that go back to prehistoric times. The oldest lamprey fossil records date back between 400 and 600 million years, well before the first dinosaurs walked the Earth. And they haven’t evolved much since, Clemens said, with prehistoric lamprey and their modern-day counterparts showing few differences.

That means the species existed mostly undisturbed for roughly half a billion years, until humans decided they were a problem in the mid-'70s.

And the problem they were thought to cause wasn’t even real in the first place, Clemens said. Despite the fact that they feed parasitically on trout, there’s no evidence they pose any risk to the larger game fish, or to humans for that matter, according to Clemens.

They do, however, provide a number of environmental benefits; they create habitat for aquatic insects, recycle nutrients and act as prey for larger fish, birds and mammals.

That’s what makes the lamprey’s return to its native lake such a big win, Clemens said.

"It's tremendously exciting,” he said. “This is happening faster than we anticipated and especially these days with lots of doom and gloom news it's good to experience firsthand a positive outcome with conservation."