PORTLAND, Ore. -- Half of all the inmates in the Multnomah County Jail suffer from some form of mental illness according to staff.

They say it's often tied to our homeless and opioid crisis. In the past year, a remodel of their mental health wing has produced some great results in stabilizing inmates' moods while in custody.

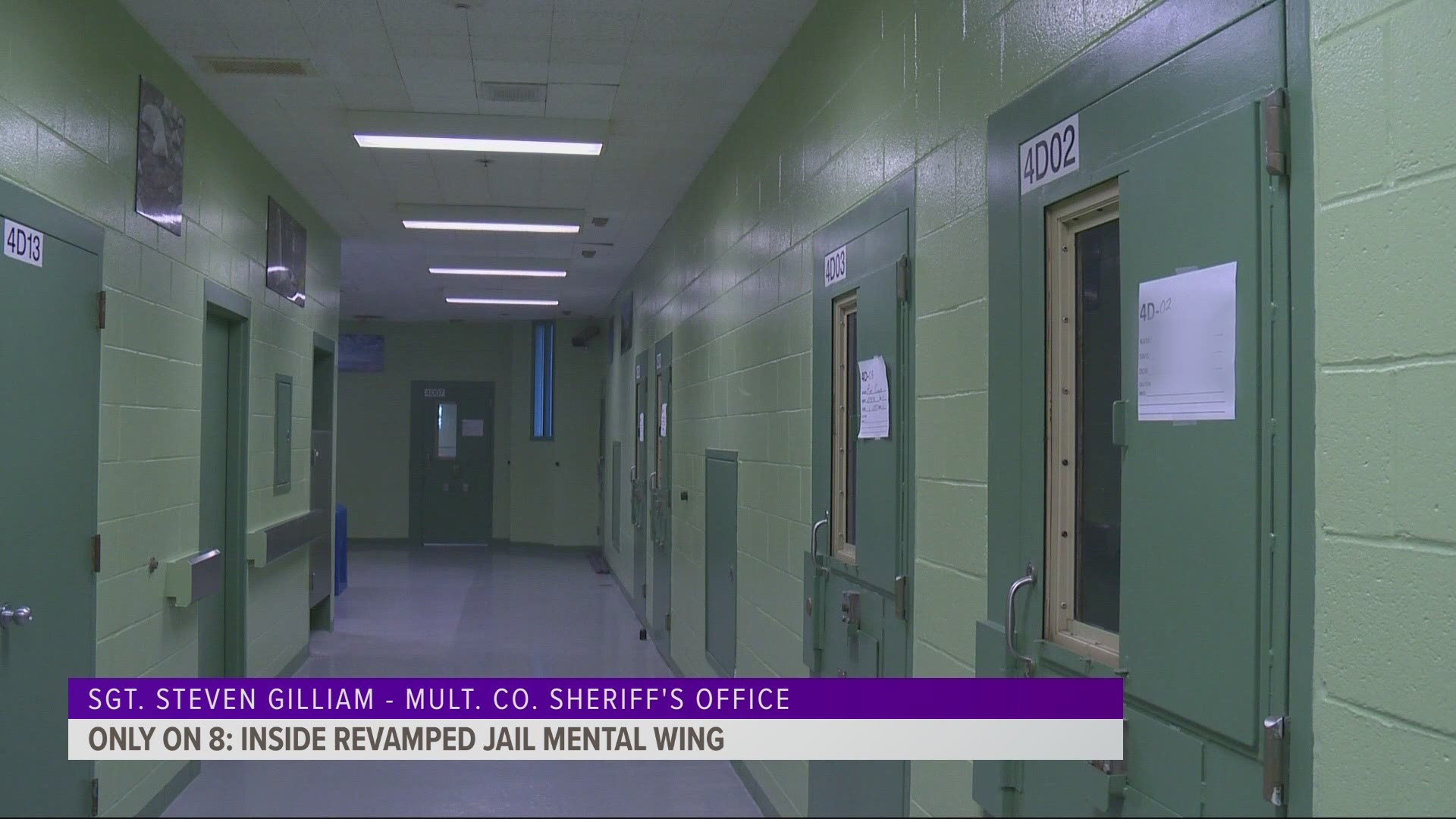

The Multnomah County Sheriff's Office gave KGW special access to the revamped mental health wing of the downtown Justice Center jail. What used to be 10 cells for mental issues in the 1990s, is now 157 cells spread out over three floors.

Behind any jail cell door, lies a lot of issues. Sgt. Steven Gilliam says the number of mentally ill inmates has exploded. Gilliam showed KGW a wing housing the five inmates who were determined to be the most violent and mentally ill. He says they're only let out three times a week for 15 minutes at a time because they consistently assault deputies, themselves and throw feces and urine.

In 2017, a probationary sergeant decided to propose a slight makeover of wing 4-D. She met with psychiatrists to try a new, aesthetic approach that might calm aggressive inmates while locked up.

Her proposal was granted and they painted walls pastel green and blue, instead of the drab gray that's on every other floor of the downtown jail. They got rid of the stainless steel table and attached chairs, in favor of brightly colored blue sand-filled plastic living room-style furniture and side tables.

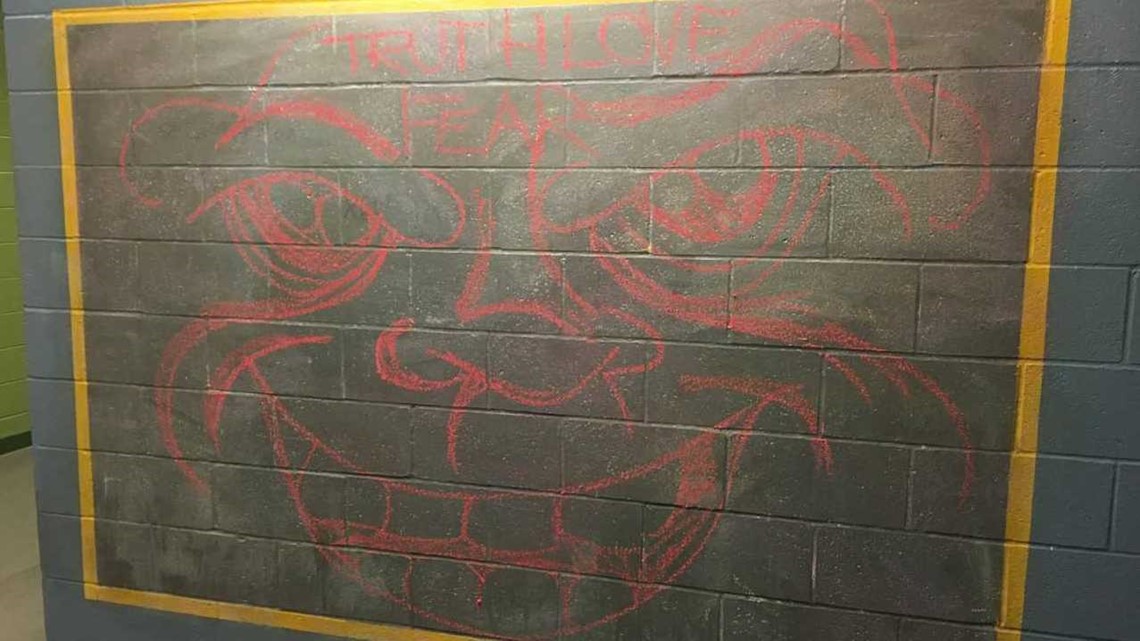

Inmates can now express themselves with colored sidewalk chalk and a huge chalkboard in the common area and in each of their cells.

"A lot of guys come out here and paint, like the picture that's there right now, or they paint in their rooms," said Sgt. Gilliam. "If you look in some of the rooms, some people have painted their entire rooms."

Some inmates have written names of loved ones on the walls. Others have huge murals they've worked on for days.

"Sometimes they draw dark stuff, and sometimes they draw happy stuff," Gilliam said.

Harsh lighting in each cell was dimmed to create a calmer mood. The lower risk mental health inmates are allowed in the common area several times a day, where music now plays.

"There's a couple guys who come out and get in the middle of the floor and start dancing. That gal in number 10, she likes to dance. She'll get out there and start dancing to the music," Gilliam said. "As long as they're happy, I'm happy. If they're doing something creative, then we let people be."

Therapy is part of the new regimen.

Staff are trained in mental health calming techniques. A psychiatrist now comes twice a week.

Myque Obiero, a registered nurse, heads the jail medical team and has seen a huge difference in demeanor in both jail staff and inmates.

"When people are acutely aware that they're not dealing with just behavior itself, but you're dealing with a person, it's a more holistic approach," Obiero said.

Even though society now treats it as such, the jail is not a mental hospital.

"We're not trying to cure people, we're just trying to get them through the court process," Gilliam said.

There is only one state psychiatric hospital left in Oregon. Judges refer some non-violent inmates there, but their stay is only temporary. Then, they're usually just let back out where they're homeless.

Both Gilliam and Obiero are split whether more mental institutions will help these folks, but they do agree we need services on the streets.

"On the one hand, you can say we have this homeless, mental health problem; somebody's got to do something, but again who is that somebody and who pays for it?" Obiero said. "We don't need another jail. I don't think we need another mental institution. I think we need more education and alternative ways of dealing with things at the root cause, like can we reach out to them on the street?"

Gilliam would like to see a more rigid approach.

"They're here for an extended period of time and they're stabilized while they're with us, but they're not getting cured because we're not the people to do that. We need a state hospital that we can send these people to and get their diagnosis cured before they can go to the courts."